Reflections on Data Science & Machine Learning

After graduating from the UBC Master of Data Science program for almost a year, I decided to do some reflections on my personal experience so far. For all readers, I hope you may find this relatable based on your own journey.

1. All models are wrong but some are useful

This quote by George Box has been resurfacing in my thoughts over the past year as I grappled around the idea of causality in the space of machine learning (ML).

While doing self-learning on Brady Neal’s Causal Inference course, there was a guest talk by Yoshua Bengio on the topic of “Towards Causal Representation Learning” where he describe the philosophical concept of “representation”. In his talk, he mentioned how a physicist might want to capture a causal model by measuring the information flow at a physical level of atoms and the forces of nature, but for other applications of causal thinking, we do not need to model information at such microsecond or atomic scales. In fact, we want to capture causal structures that are made up of “abstractions” or some form of artificial aggregated constructs that are meant to have an inherent logical representation.

Thus, even when we talk about creating models, there is nothing that can validate that one’s proposed model of a linear regression model is “universally correct”. What we are doing is actually using aggregated “abstractions” to help us understand the world, but all of that are just constructs conjured by us.

Although it might sound disheartening to know that there is no true model, it’s actually not the end of the world. One can still use these models to provide immense value. In David Blei’s talk on “Economics and Probabilistic Machine Learning”, a question posed to him during Q&A was about the concept of a “true” model. David talked about the concept of model misspecification, and brought up his idea of text topic modelling using Poisson factorisation. In his words, he states the following:

“…I don’t think there’s a true model. I think these models are all simplifications, and they’re for a purpose…I’ve done a lot of work in topic modelling with John, and we don’t believe that text comes from a topic model. That would be insane to believe that. But rather, that particular characterisation of the hidden variables in text is useful for building navigators based on themes that help someone quickly explore a massive dataset. So personally, I’m not sure there’s a true model…”

I thought that was very enlightening, and comforting as it prevented me from succumbing to the idea that every model we create is futile or pointless.

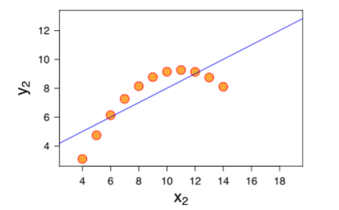

The following screenshot shows a classic example of model misspecification where visually it does show that the straight line linear regression is not able to capture the curvature of the data (probably from a higher order data generating process). As long as we predict within the support of the feature data (x-axis), the misspecified straight line model does provide reasonable results. However, extrapolating beyond the support range is definitely ill-advised.

2. Garbage in, garbage out

Most of the data science syllabus are framed in a way to teach you how to apply predictive algorithms on various datasets. A large part of my learning experience on the Internet has been centered around following package vignettes or walkthrough tutorials that utilise publicly available datasets that have been curated/approved, which promotes the learning concepts in a controlled environment.

Based on my personal experience over the past year, useful data may not always be available and you have to spend time thinking about procuring them. Depending on circumstances, your organisation may still be in a nascent stage where it has not established the right infrastructure. Just parsing through the e-book “Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments : A Practical Guide to A/B Testing” taught me that it is absolutely critical to set up the infrastructure for collecting high quality instrumentation data so that you can trust the results of any experiments. Likewise, if you are trying to create a supervised learning predictive model where the feature data dimensions are not correlated with the target variable, fitting ML models can only do so much.

Although data science has been hyped up by the “shiny” promise of machine learning predictions, the actual “value” of data science applications is affected by a lot of factors, one of which is the availability (or lack) of useful data. What I realised is that to be effective as a data scientist, beyond learning the different ML algorithms, one needs to learn the critical technical skills so he/she can:

- navigate the organisational infrastructure to access the right data if it currently exists

- propose changes to the infrastructure so that the right data can be collected if it does not exist

- ensure that the data transformation/preprocessing workflow is appropriate

On a similar note, this brings me to the next point about the implicit assumptions when using ML for modelling.

3. (In)appropriate assumptions with ML modelling

Most of the data science algorithms are meant to deal with situations where the data is stationary. If the data distribution is stationary and the observations are independent and identically distributed (iid), then various ML algorithms can be applied to provide the necessary inference or predictions. A key philosophy of model fitting using cross validation techniques to ensure performance generalisation, which also highlights the idea that the data are exchangeable and comes from a stationary distribution.

Just thinking about my past experience as a chemical engineer, I used to deal with thermodynamics and equations that were considered “laws”. Behind this mindset or thinking came with a huge set of assumptions: the observations collected (whether be it a temperature or pressure reading) came from an underlying universal data-generating process that followed some stationary “natural” phenomenon, and it was up to me as an engineer to provide solutions for yield optimisation or even human safety by analysing the data collected.

However, data science has been applied on various fields where the data distributions are highly not invariant. Think about data science applications centered around human behaviour. In our society, there has always been a constant shift/evolution in the aggregate consciousness be it on a global level or a local/regional level. What was trendy previously 5 years ago may no longer be fashionable, and this has implications on recommenders system used in e-commerce platforms.

When it comes to globalisation, we see a confluence mix of cultures which can simultaneously erode existing languages or result in the emergence of novel lingo (“yeet”!). Assuming there is indeed an underlying true data generating process that can be modelled (See Point 1) via NLP applications, this means that the generating process is evolving with time. Identifying covariate shift is actually an extremely difficult task in my opinion, and I would love to find out more in dealing with it.

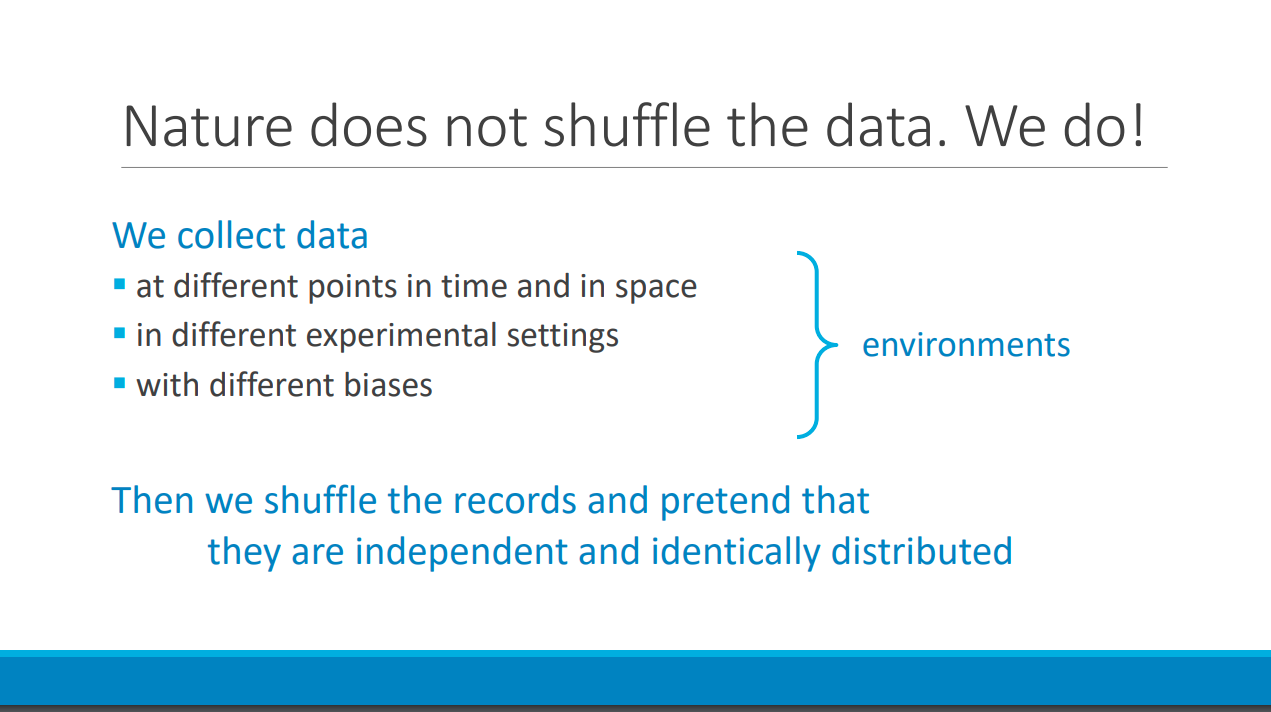

I also want to point out that there are certain applications where the dataset is curated but yet assumed to come from some form of “natural” distribution before applying ML statistical modelling for prediction. For example, one may scrape various images from the internet to do an image classification task. If you think more about it in detail, there is nothing “natural” in those images. Those images are generated from someone who decided to choose to capture a photo of a particular object (perhaps in a certain angle or lighting or special occasion). There is an inherent selection bias in terms of the data generated, and to simply use ML algorithms with the assumption that the data is iid is actually at best inappropriate. For an indepth reference, see this talk “Learning Representation Using Causal Invariance” by Leon Bottou. Below shows a particular slide from his talk which illustrates the above point. His slides can be found here

Think hard about what you’re doing

In summary, model misspecifications, availability of useful data, and assumptions of ML modelling are easily overlooked and can actually affect the results of your data science application. However, by applying more deliberate critical thinking and logic, one can acknowledge the actual potential and limitations of the “supposed” value that a data scientist can contribute to your organisation. Building on that notion, I think organisations with a diverse team and healthy discussion forums actually help to anchor, correct and manage the expectations of various (internal or external) stakeholders regarding the value of data science.

If you have made it this far, thanks for reading! I hope that you found this post relatable based on your experience. Beyond that, I would love to hear more about anybody’s experience or insights so feel free to leave a comment!